The more I explore the psychology of loneliness, the more I uncover subtle, surprising ways it intertwines with human survival. This curiosity led me to revisit Games People Play: The Psychology of Human Relationships by Canadian psychiatrist Eric Berne, hoping to find a “game” that might illuminate the experience of loneliness.

Drawing on his theory of Transactional Analysis, Berne shows how we shift between our Parent, Adult, and Child ego-states — friend or foe, mentor or rebel, protector or suppressed dreamer — and how these internal roles manifest in patterned, unconscious interactions. Like most unconscious behaviours, these ego-states aim to meet fundamental human needs — particularly those for intimacy and recognition.

At the heart of Berne’s book is the idea that many everyday interactions follow predictable “mind-game” scripts: from the passive-aggressive Kick Me, to the avoidant dance of Why Don’t You – Yes But, or the classic marital script If It Weren’t For You. Though they may seem harmless — or even entertaining — these games often function to preserve psychological equilibrium, secure social validation, or gain control in relationships.

We can easily understand how insufficient emotional or sensory nourishment leads to physical and psychological decline. But Berne introduces another survival mechanism that is perhaps less obvious: our deep need for structure.

“[Structure] satisfies the human need to avoid boredom … If it persists for any length of time, boredom becomes synonymous with emotional starvation and can have the same consequences.”

Academic and podcaster Brené Brown echoes this in Atlas of the Heart, where she defines boredom as “the uncomfortable state of wanting to engage in satisfying activity, but being unable to do it.” She quotes psychologist and technology Sherry Turkle:

“Boredom is your imagination calling for you.”

Berne believes that human beings constantly face the challenge of structuring their waking hours — and that from an existential perspective,

“The function of all social living is to lend mutual assistance for this project.”

The two most satisfying forms of social contact, he argues, are games and intimacy. In this context, intimacy means the “spontaneous, game-free candidness of an aware person… the uncorrupted Child in all its naïveté, living in the here and now.” It’s a rare, psychologically autonomous state that healthy humans strive to reach.

Importantly, Berne notes that social games are passed from generation to generation. They hold cultural significance:

“‘Raising’ children is primarily a matter of teaching them what games to play. Different cultures and different social classes favour different types of games, and various tribes and families favour different variations of these.”

This presents a compelling lens on modern individualism: we aren’t just social beings, we’re players in elaborate, often invisible, societal “games.” In a culture that prizes personal freedom and self-expression, we may present as fully autonomous Adults, while unknowingly acting from scripts shaped by our upbringing and social norms. These scripts reward self-reliance, deflect intimacy, and subtly reinforce individualist ideals.

According to Berne, true authenticity arises when we engage in Adult-to-Adult communication — when we break free of the games and step into awareness, spontaneity, and genuine connection.

So where does loneliness fit into all this?

A coherent (and entertaining) explanation comes from Dr. K, an American psychiatrist and mental health coach, in his video on Loneliness – The struggle we all feel. He describes how today’s society is not only increasingly stressful, but also “dependent on independence.” Under stress we become more vulnerable and tend to withdraw into safe spaces — physically or emotionally. This very instinct for self-preservation often isolates us, creating a spiral of loneliness.

However, loneliness is a problem that an individual cannot fix on their own, since the very antidote to loneliness is meaningful, reciprocal connection. And yet, in a society where individualism is prized, we subtly distance ourselves from the responsibility of caring for others. The inner logic becomes: “This is not my problem.”

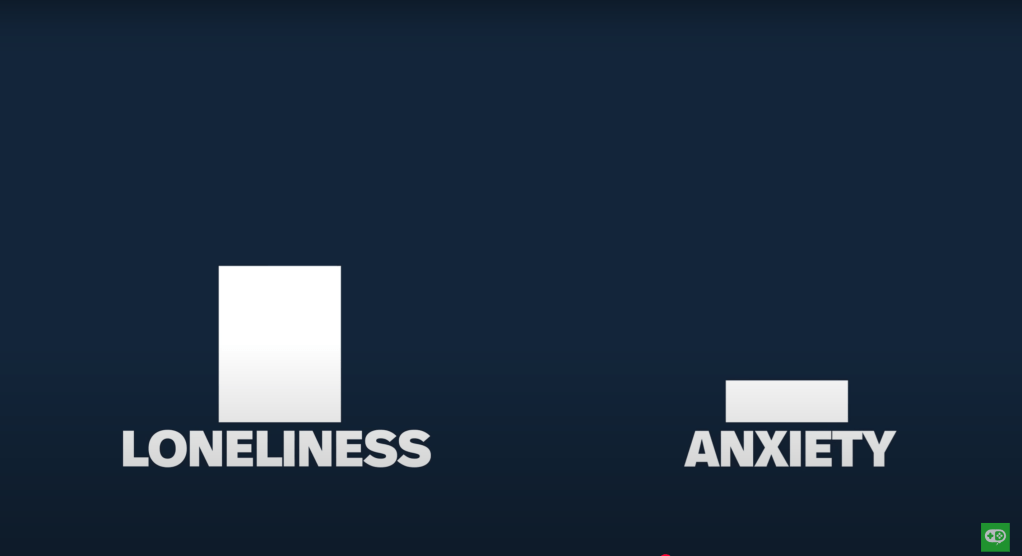

The more this mindset spreads, the harder it becomes for a lonely person to reach out. Their longing for connection is now entangled with the anxiety of whether it will be welcomed or rejected. The result is a kind of internal equation — a psychological game of balancing loneliness versus anxiety. In order to feel less lonely, the individual must risk greater vulnerability. Too much anxiety, however, leads to withdrawal… and the cycle continues.

Dr. K suggests a powerful, counterintuitive shift: even if you are lonely, begin by focusing on someone else’s struggle. Service to others, even in small, quiet ways, can help reduce the feeling of disconnection. This idea may seem foreign in a culture that teaches us to think individualistically. But as Berne’s work reveals, we are not just shaped by these social games — we also have the capacity to outgrow them.

By recognising the scripts we’ve inherited, by daring to break free from the “games,” and by choosing meaningful, vulnerable connection over performance or control, we open a pathway — not just out of loneliness, but toward something deeper: a more authentic, shared humanity.